- Industry News

10 Common Mistakes Beginners Make When Choosing Electronic Components (and How to Avoid Them)

- By tian81259@gmail.com

When you’re just getting started with electronics, choosing the “right” components can feel harder than designing the actual circuit. The schematic looks simple, the YouTube tutorial was clear — but your prototype still runs hot, behaves weirdly, or fails after a few days.

In many cases, the problem isn’t your idea. It’s your component selection.

Below are the 10 most common pitfalls beginners hit when selecting electronic components, plus practical tips to avoid them in your next project. Where useful, you’ll also find links to deeper guides and manufacturing tools you can explore later.

1. Ignoring Voltage and Current Ratings

One of the biggest beginner mistakes is treating components like Lego bricks: “If it fits, it works.” In reality, every part has maximum ratings you can’t cross.

Typical problems:

- Using a 16 V electrolytic capacitor on a 24 V supply

- Driving a 200 mA motor with a 100 mA-rated transistor

- Powering a 12 V relay from a 24 V supply

If you’re still unsure how to read and compare these numbers, a dedicated parameter guide such as an electronic component parameter guide can help you quickly understand voltage, current, and power ratings in real projects.

What to check:

- Maximum voltage (Vmax) – supply voltage, signal amplitude, spikes

- Maximum current (Imax) – continuous vs. peak current

- Safety margin – keep at least 20–30% headroom above your normal operating point

Quick rule:

- Maximum voltage (Vmax) – supply voltage, signal amplitude, spikes

- Maximum current (Imax) – continuous vs. peak current

- Safety margin – keep at least 20–30% headroom above your normal operating point

Quick rule:

If your circuit runs at 12 V and draws 500 mA, choose components comfortably rated for at least 15–16 V and 700–800 mA.

2. Forgetting About Power Dissipation and Heat

Even if voltage and current look “OK,” your part can still overheat. That’s where power dissipation (P) and thermal resistance come in.

Classic beginner issues:

- A 1/4 W resistor used where it actually needs to dissipate 0.5 W

- Linear regulators (e.g., 7805) getting too hot when dropping a large voltage

- MOSFETs without heatsinks in high-current applications

Basic formula:P=V×I]orforresistors:\[P=RV2=I2×R

If you calculate 0.4 W on a resistor, don’t use a 0.25 W part. Jump to 0.5 W or 1 W and consider airflow or heatsinking.

When you scale up from hobby projects to small production runs, thermal design becomes even more critical — especially if you later plan to use automated equipment like an electronic component forming machine to shape and mount parts consistently on PCBs.

Checklist:

- Compute worst-case power (not just typical)

- Check maximum power rating in the datasheet

- Consider ambient temperature and enclosure (no airflow = hotter components)

3. Choosing the Wrong Package or Footprint

On paper, a part may be perfect. On your actual board or breadboard, it might be impossible to use.

Common headaches:

- Buying only SMD parts when you plan to build on a breadboard

- Choosing a footprint that doesn’t match the PCB footprint in your design

- Using oversized components that don’t physically fit in the enclosure

If you’re not yet comfortable with the big picture of resistor, capacitor, inductor, diode, and IC families — and their common packages — a foundational article like an electronic components category guide can help you understand which package types are beginner-friendly and which ones are better suited to automated production.

How to avoid it:

- Decide early: through-hole vs. SMD

- Check the package carefully (e.g., SOIC vs. TSSOP vs. QFN)

- Verify the pin spacing and outline dimensions against your PCB design

- When in doubt, print the PCB at 1:1 scale and test-fit components on paper

For beginners, starting with through-hole components is usually simpler for prototyping and hand soldering.

4. Misunderstanding Tolerance and Accuracy

Not all resistors and capacitors are created equal, even if they share the same nominal value.

Typical misunderstandings:

- Using a 5% resistor in a precision measurement circuit

- Selecting a ±20% capacitor for a timing circuit and wondering why the timing drifts

- Ignoring tolerance in voltage dividers and reference circuits

What tolerance means:

A 10 kΩ ±5% resistor can be anywhere between 9.5 kΩ and 10.5 kΩ. That variation stacks up when multiple parts interact.

When tolerance really matters:

- Oscillators and RC timing circuits

- Reference voltages and sensor front-ends

- Precision analog measurements

If your circuit needs accuracy, use 1% or even 0.1% resistors, and better-tolerance capacitors designed for timing or stability.

5. Overlooking Frequency and Speed Limits

Many components behave differently at higher frequencies or speeds. Beginners often design around DC specs and forget about dynamic behavior.

Examples:

- Using a low-bandwidth op amp in a high-frequency signal path

- Choosing capacitors without checking ESR and impedance vs. frequency

- Using inductors that saturate or perform poorly at switching frequencies

Key specs to watch:

- Gain bandwidth (GBW) and slew rate for op amps

- ESR (Equivalent Series Resistance) and self-resonant frequency for capacitors

- Core material and saturation current for inductors in switching regulators

If you’re working with switching power supplies, RF modules, or fast digital signals, double-check frequency-related parameters before ordering.

6. Using the Wrong Type of Capacitor

Capacitors are not interchangeable. Different types behave very differently.

Common mistakes:

- Replacing a polarized electrolytic with a ceramic at the same value without checking voltage or ripple current

- Using a ceramic capacitor in an audio signal path where a film capacitor would sound and perform better

- Ignoring polarity on electrolytic or tantalum capacitors (and watching them fail dramatically)

General guidelines:

- Ceramic capacitors: great for decoupling, high-frequency filtering, small values

- Electrolytic capacitors: great for bulk energy storage on power rails (higher capacitance, polarized)

- Film capacitors: ideal for audio, precision, and low-loss applications

Always check: type, voltage rating, ESR, and polarity.

7. Not Reading MOSFET and Transistor Datasheets Carefully

MOSFETs and BJTs look simple on a schematic, but their real-world behavior can be tricky.

Frequent errors:

- Using a MOSFET that is not logic-level, so it doesn’t fully turn on at 3.3 V or 5 V gate drive

- Ignoring Rds(on) and ending up with excessive heat at higher currents

- Forgetting about gate charge (Qg) and slow switching in high-frequency applications

- Using BJTs without checking gain (hFE) and saturation behavior

What to check for MOSFETs:

- Gate threshold voltage (Vgs(th)) is not the turn-on voltage — you need higher Vgs for low Rds(on)

- Rds(on) at your actual gate voltage (e.g., 4.5 V or 10 V)

- Maximum drain current (Id) and power dissipation

- Package and required heatsinking

If you need a practical, purchasing-focused overview of how to translate datasheet specs into real buying decisions, a resource like an electronic components purchasing guide is a good next step.

Spend a few extra minutes reading the datasheet curves — it will save you hours of debugging.

8. Underestimating Inrush Current and Transients

The real world is noisy. Power supplies glitch, motors create spikes, and cables pick up interference. Beginners often design for ideal conditions only.

Typical oversights:

- No flyback diode across relays or motors

- No TVS diodes or surge protection on external connectors

- Forgetting about inrush current when large capacitors charge at power-up

Practical protections:

- Use flyback diodes with inductive loads (motors, relays, solenoids)

- Add TVS diodes, series resistors, or filters on external I/O lines

- Consider NTC inrush limiters or soft-start circuits for large capacitive loads

Designing for transients makes your project more robust and less prone to random resets or damage.

9. Ignoring Environment, Lifetime, and Reliability

A circuit that works perfectly on your desk may fail quickly in the real world.

Things beginners forget:

- Temperature range (consumer vs. industrial vs. automotive grade)

- Humidity, dust, and mechanical vibration

- Component lifetime, especially for electrolytic capacitors and relays

What to consider:

- Where will the product live? Indoors, outdoors, in a car, near heat sources?

- Choose components rated for the expected temperature range and conditions

- Check lifetime specs for capacitors (e.g., 2,000 h at 105°C) and derate appropriately

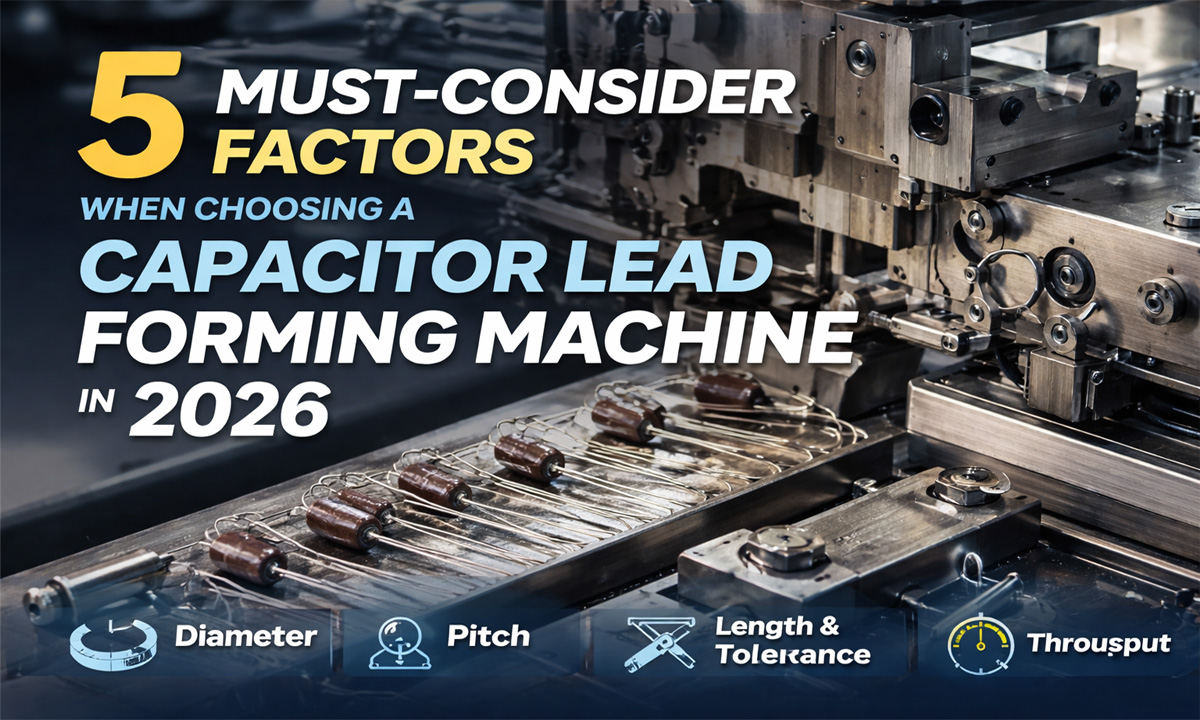

For professional or semi-industrial products, it’s also worth planning early for how components will be cut, formed, and inserted in production. Using dedicated equipment such as a lead forming machine can help keep mechanical stress under control and improve long-term reliability.

10. Buying Only the Cheapest Parts With No Supply Strategy

Beginners often sort by “lowest price” and order whatever looks right. That’s risky, especially for projects that may need maintenance or scaling later.

Common problems:

- Parts become unavailable or obsolete after a few months

- No second source (only one obscure brand or part number)

- Quality issues with unknown suppliers

Better approach:

- Prefer components from reputable brands and distributors

- Check if there are drop-in equivalents (same package, similar specs)

- Avoid parts marked “NRND” (Not Recommended for New Designs) or “EOL” (End of Life)

If you already know that a design may go into small-batch or mass production later, think ahead about tooling, forming, and assembly from the very beginning. That way, shifting from breadboard to automated lines and electronic component forming equipment will be much smoother.

A Simple Checklist for Smarter Component Selection

Before you click “Buy,” run through this quick beginner-friendly checklist:

- Voltage & current: Do all parts have at least 20–30% headroom?

- Power & heat: Did you calculate power dissipation and think about cooling?

- Package: Will the components fit your breadboard/PCB/enclosure?

- Tolerance & precision: Do critical parts have tight enough tolerance?

- Frequency behavior: Are the parts suitable for your signal or switching frequency?

- Capacitor type: Is the type and polarity correct for the job?

- MOSFET/BJT details: Did you check Rds(on), Vgs, hFE, and thermal limits?

- Protection: Do you have flyback diodes, surge protection, and filtering where needed?

- Environment: Are parts rated for the temperature and conditions they’ll see?

- Supply & lifecycle: Are your chosen parts reliable, available, and not near EOL?

Final Thoughts

Learning electronics isn’t just about wiring up circuits — it’s about understanding how and why components behave the way they do. If you slow down and check these 10 areas when selecting parts, you’ll:

- Burn fewer boards

- Spend less time debugging “mystery” failures

- Build circuits that are safer, more reliable, and easier to scale

From basic parameter reading to purchasing decisions and even mass production with automated lead forming equipment, every step you optimize today will make your future projects more professional and more reliable. As you gain experience, reading datasheets, checking ratings, and thinking about real-world conditions will become second nature — and your designs will start to look a lot like what the pros build.

Related Posts

20 Years of Expertise, Trusted by Clients Worldwide

The Preferred Choice of Foxconn, BYD, and Huawei