- Industry News

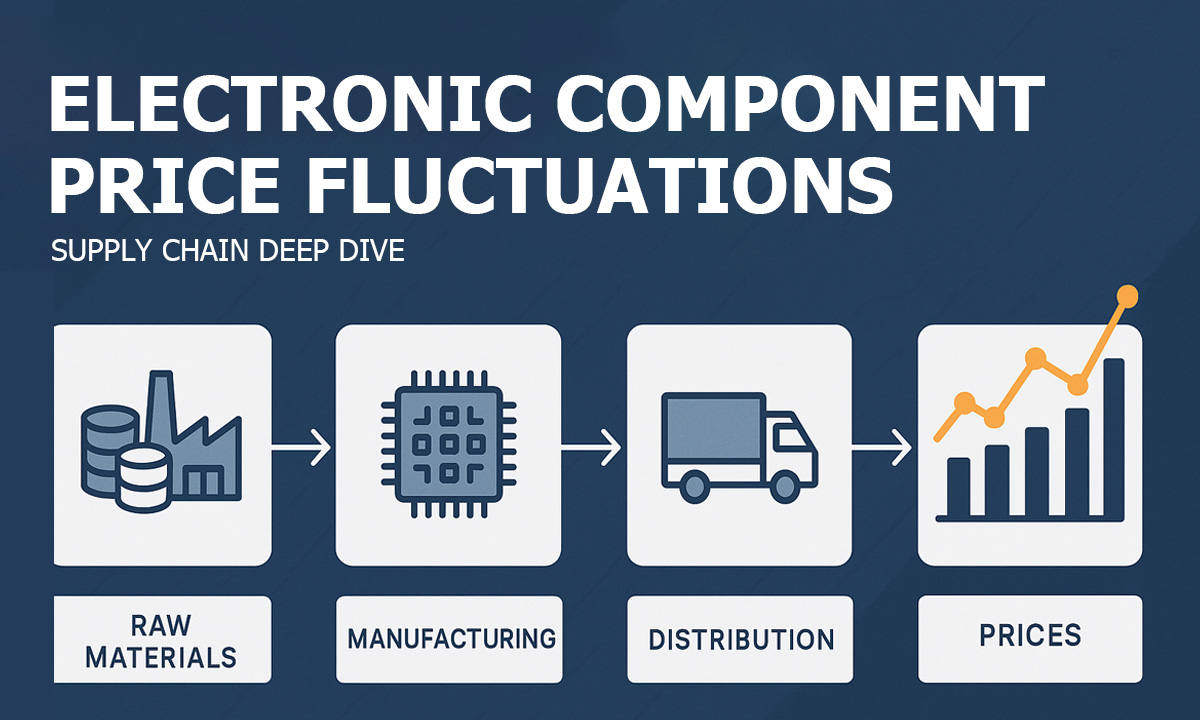

Where Do Electronic Component Price Fluctuations Come From? A Supply Chain Deep Dive

- By tian81259@gmail.com

Price lists for resistors, capacitors, MOSFETs, and ICs rarely stay still for long. One month a key regulator is “easy to buy,” the next month the price doubles and lead time stretches to 26 weeks. For buyers and engineers, these swings feel random — but they actually follow a fairly clear supply chain logic.

Below is a practical, business-focused look at where electronic component price volatility really comes from, and what you can do to manage it rather than just react to it.

- Why Electronic Component Prices Move So Much

Electronic components sit at the intersection of three forces:

- Global raw material markets (copper, aluminum, precious metals, rare earths, silicon wafers)

- Highly capital-intensive manufacturing (fabs, passive component lines, packaging houses)

- Cyclical end-user demand (consumer electronics, automotive, industrial, energy, telecom)

When any of these three moves sharply, prices ripple through the entire chain. The further you are from the source of the problem, the more “sudden” those price changes feel.

- Raw Materials: The First Wave of Price Pressure

Most components are built on a small set of basic materials:

- Copper and aluminum for leads, terminals, bus bars, and PCB traces

- Nickel, tin, silver, and gold for plating

- Ferrite and iron powders for magnetics

- Ceramic powders for MLCCs and other capacitors

- Silicon wafers and specialty gases for semiconductors

- Plastics and resins for housings and encapsulation

When these material prices rise because of mining constraints, energy costs, geopolitical events, or environmental regulations, component makers have three options: absorb the cost, improve yield, or raise prices. In tight-margin segments (like commodity resistors or general-purpose capacitors), they usually end up raising prices.

The impact isn’t always immediate. Major manufacturers often sign quarterly or annual supply contracts for metals and wafers. Once those are renewed at higher levels, the new cost base gradually shows up on component price lists and distributor pricing.

- Manufacturing Capacity: When Fabs and Lines Are Fully Booked

Even if material costs stay flat, capacity can drive price movement:

- Semiconductor fabs: When advanced nodes are full of high-margin chips (smartphones, GPUs, automotive MCUs), lower-margin parts can be deprioritized, limited, or repriced.

- Passive component lines: MLCC, resistor, and inductor factories run at very high utilization when demand is strong. Any surge — EVs, 5G base stations, new game consoles — can push them from “busy” to “booked.”

- Investment cycles: Building new fabs or high-volume lines requires billions of dollars and years of lead time. Capacity cannot be expanded overnight.

When demand outstrips practical capacity, manufacturers often move from “open market” pricing to allocation. Key accounts with long-term contracts get stable pricing and volumes; the rest of the market ends up competing in a tighter supply pool, and prices climb.

- Yield, Quality Requirements, and Product Mix

Not every wafer or production batch turns into salable parts. Yield losses and quality requirements matter:

- Stricter automotive or industrial reliability standards can reduce effective yield, raising cost per usable component.

- Complex ICs and power devices have higher scrap risk; when yield drops, cost per good die goes up.

- If a line shifts to higher-margin, higher-spec product (for automotive or medical), standard-grade versions may become more expensive or simply less available.

For buyers, this often shows up as “we still have stock, but only the automotive grade” — at a significantly higher price.

- Logistics, Freight, and Geopolitics

Even if components are cheap at the factory gate, getting them to your warehouse can be costly and unpredictable:

- Ocean freight rates can spike because of port congestion, regional conflict, or capacity shortages in shipping lanes.

- Air freight becomes more expensive when fuel prices rise or belly cargo capacity declines.

- Customs delays, tariff policy changes, and export controls add both cost and risk.

When logistics become unreliable, manufacturers and distributors add a risk premium to pricing. In some cases, they must reroute shipments through longer paths, directly increasing landed cost.

- Currency and Interest Rates

Most electronic components are priced in US dollars. If your local currency weakens against the dollar, your effective price goes up even if the factory price stays flat.

At the same time, higher interest rates make inventory more expensive to hold. Distributors and OEMs tend to reduce stock, which can amplify price swings:

- When demand suddenly rises, low inventory means rapid shortages and sharp price increases.

- When demand falls, excess inventory triggers discounting and price cuts.

Managing this balance is a big part of strategic procurement. A more detailed breakdown of this financial side sits naturally next to a broader sourcing strategy, such as the one outlined in our electronic component procurement guide

- Demand Shocks: When End Markets Move Together

On the demand side, big swings come from a few familiar places:

- Consumer electronics cycles: New smartphone generations, game consoles, and PCs can create huge but temporary demand.

- Automotive and EVs: Each EV uses far more power electronics and control boards than a traditional car. When EV volumes jump, they pull large volumes of IGBTs, MOSFETs, MCUs, and passive components.

- Industrial and energy: Inverters, charging piles, solar inverters, and industrial power supplies each consume significant quantities of power semiconductors and high-reliability passives.

- Telecom and data centers: 5G rollouts, new base stations, and AI server deployments add heavy demand for specialized ICs and RF components.

When several of these sectors heat up at once, general-purpose components (MLCCs, resistors, common power ICs) can get squeezed, driving broad price increases.

- Distributors, Brokers, and the Spot Market

Between the factory and your warehouse, there’s another layer that shapes pricing:

- Authorized distributors: They balance long-term contracts and forecasted demand. In normal times, pricing is relatively stable and transparent.

- Brokers and the gray market: During shortages, more volume flows through brokers. Prices reflect immediate supply and demand — and the need to cover higher risk and quality control efforts.

- Allocation rules: When manufacturers put parts on allocation, distributors decide which customers get what. Long-term, high-volume partners get priority; spot buyers pay more.

This is why two buyers can see completely different offers for the same part on the same day.

- Customer-Side Factors: Specifications, Flexibility, and Process

Price volatility is not only “out there” in the market. Internal decisions inside your organization also influence how exposed you are:

- Over-specifying parts: Using automotive or industrial grades where commercial grade would suffice locks you into higher-cost components.

- Single-sourcing: Designing boards around one specific part (or even one vendor) makes you vulnerable when that part goes short.

- Narrow approved vendor lists (AVL): If your AVL is too tight, it limits your ability to switch when prices move.

- Manual, slow processes: If engineering and procurement cannot quickly evaluate and approve alternates, you miss chances to avoid spikes.

Standardizing common components and opening up your AVL are simple ways to reduce exposure. A lot of this thinking is already embedded in structured selection checklists like the ones summarized in our electronic component selection guide

- How Manufacturing and Automation Feed Back Into Pricing

For many power electronics and control board products, the cost of the component is only one part of the total picture. Assembly, forming, and reliability also matter:

- If your process relies heavily on manual lead cutting and forming, labor and scrap costs can rise when you switch to alternate components with different lead spacing or package shapes.

- Automated forming and trimming equipment allows you to adapt to alternate parts more easily, because it can be re-tooled or re-programmed instead of requiring fully manual rework.

- Better process control reduces damage during forming and soldering, which actually lowers your effective cost per usable component even when unit prices are up.

This is why many factories that struggle with volatile BOM costs eventually look at automation solutions like resistor lead forming machines and other electronic component forming equipment. Lower process variation and less manual handling can offset part price increases by reducing hidden scrap and rework.

- Practical Strategies to Manage Price Volatility

Knowing where price swings come from is only useful if you turn it into action. A few practical strategies:

- Build a risk map for key parts

Identify which components are highest risk in terms of single sourcing, long lead time, and technical uniqueness. Focus your mitigation efforts there. - Broaden your approved component list

For resistors, capacitors, and standard semiconductors, qualify alternates from multiple vendors wherever possible. Make it easy for engineering and procurement to switch when needed. - Mix contract and spot buying

Use long-term agreements for truly strategic parts, and leave room to exploit spot opportunities for less critical items. - Stay close to authorized distributors and manufacturers

Regular communication gives you early warning about upcoming price changes, allocation decisions, and capacity constraints. - Invest in process flexibility

If your production line can handle a range of lead forms, package shapes, and assembly methods with minimal downtime, you are less exposed when you need to change parts quickly.

- Conclusion

Electronic component price fluctuations rarely come from a single cause. They are the product of raw material trends, factory capacity, logistics, currency, demand cycles, and decisions made inside your own organization.

You cannot control global copper prices or build your own wafer fabs, but you can decide how exposed your BOM is to shortages, how flexible your production process is, and how quickly you can pivot when the market turns.

The teams that treat pricing volatility as a structural supply chain issue — rather than a series of “bad surprises” — usually end up with more stable costs, fewer line-down emergencies, and stronger negotiating power over time.

Related Posts

20 Years of Expertise, Trusted by Clients Worldwide

The Preferred Choice of Foxconn, BYD, and Huawei