- Blog

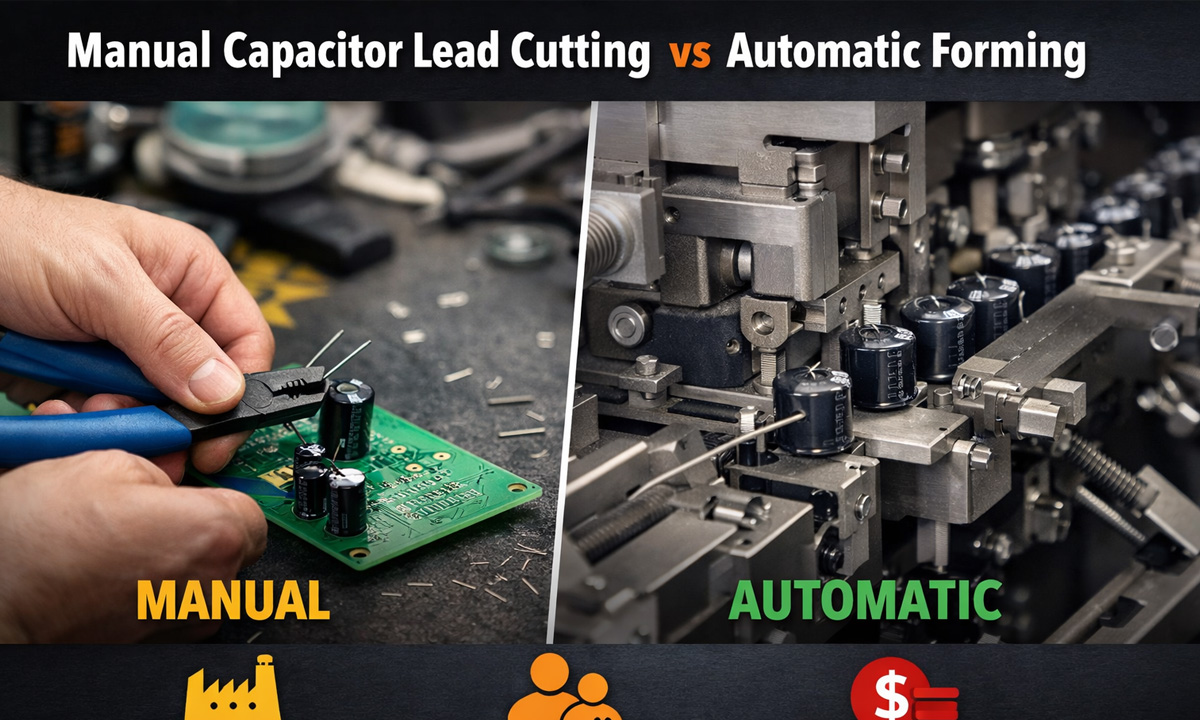

Manual Capacitor Lead Cutting vs. Automatic Forming: Throughput, Labor, and Rework Cost Compared

- By tian81259@gmail.com

If you’re still cutting capacitor leads by hand, you’re not just paying for labor—you’re paying for variability. The real cost usually shows up later as uneven lead length, bent leads, skewed insertion, unstable wave-solder results, and extra touch-up/rework. Quality organizations often quantify those “hidden” losses as part of Cost of Poor Quality (COPQ)—internal failure (rework/scrap) and external failure (returns), not just inspection time.

If you’re evaluating automation, start here: Capacitor lead forming machine and the capacitor forming machine buying guide.

1) Capacity: What you can realistically ship per shift

Manual cutting can look “cheap” when you only count wages. But it scales linearly: more output = more people, more training, more inconsistency. Automation scales better: once setup is stable, output is mainly limited by feeding and downstream insertion.

| Item | Manual cut (hand tools / simple fixtures) | Automatic cutting + forming |

|---|---|---|

| Output scaling | Add operators | Add machine hours / feeders |

| Consistency (lead length & pitch) | Operator-dependent | Program/tooling-dependent, repeatable |

| Bottleneck risk | Fatigue, turnover, peak orders | Changeover time, tooling, feeding |

| Best fit | Low volume / prototyping | Medium-to-high volume / stable SKUs |

Experience-based rule of thumb (shop-floor reality):

If you frequently hear “we can catch up by adding two temps,” you’re already in a manual capacity trap. Automation turns that into “run an extra shift” instead of “hire and retrain again.”

2) Labor: Direct labor is only half the story

Manual cutting typically needs:

- More headcount (operators + inspector + someone to fix “small issues”)

- More training time to keep length/pitch consistent

- More line-side interruptions (mis-cuts, bent leads, mixed lots)

With automation, you often shift labor from repetitive cutting to:

- Setup/changeover

- Simple in-process checks

- Material handling (bulk to feeder)

This is why many factories track scrap/rework as part of Cost of Quality—because labor “savings” disappear when defects rise.

3) Rework & returns: where the hidden cost explodes

In through-hole production, lead condition impacts solder quality and appearance. IPC-related guidance commonly emphasizes adequate wetting/fillet formation on the lead; inconsistent lead protrusion or bent leads can make meeting acceptance criteria harder and increase touch-up.

Common rework drivers with manual cutting

- Uneven lead length → insertion depth varies → inconsistent solder fillet

- Bent/over-stressed leads → micro-cracks → later intermittent failures

- Skewed components → “leaning” on PCB → cosmetic rejects or assembly interference

- Mixed spec (different pitch/length in the same bin) → line stops + sorting

Quality organizations routinely describe COPQ as a meaningful percentage of operations/sales (often double digits), because rework/scrap and failure handling consume real capacity.

4) A simple cost model you can use today

Use this quick comparison to decide if automation is financially obvious:

Manual annual cost (simplified)

- Operators needed per shift × hourly rate × hours/year

- + extra inspection time

- + rework time (touch-up, sorting, re-run)

- + scrap (materials + lost capacity)

Automatic annual cost (simplified)

- Depreciation/lease + maintenance + tooling

- + 1 setup/line operator time (often shared across stations)

- + energy + spares

- – reduced rework/scrap

If your rework/scrap is “small but constant,” that’s exactly what COPQ frameworks try to quantify: internal failure costs that look minor per unit but become huge at scale.

5) When manual cutting still makes sense

Manual is rational when:

- You’re in prototype / engineering validation mode

- Volumes are low and SKUs change daily

- Lead-forming requirements are not strict (no tight insertion/appearance spec)

- You don’t have stable packaging/feeding for automation yet

But once you have repeat orders, manual usually becomes a throughput ceiling and a quality risk multiplier.

6) How to choose the right automation level

Use these decision triggers:

- High labor pressure or turnover → automate first (manual quality drifts with people)

- Wave-solder touch-up increasing → automate to stabilize lead length/pitch

- Frequent “leaning” capacitors or insertion jams → automate forming consistency

- Stable top 10 SKUs (80% of volume) → automation ROI becomes straightforward

Next step: compare machine types and feeding options in this capacitor forming machine buying guide, then shortlist by your lead length/pitch tolerance and changeover frequency. For machine categories, see Capacitor lead forming machine.

FAQ

Is automation only about speed?

Speed is the visible win. The bigger win is repeatability, which reduces rework and stabilizes downstream solder quality—exactly the costs captured in COPQ models.

What’s the most common ROI mistake?

Counting only operator wages, and ignoring:

- line stoppages,

- sorting,

- rework/touch-up,

- scrap,

- and schedule risk from human variability.

Do standards really matter for lead length?

In practice, acceptance criteria focus on solder wetting and fillet formation on the lead, and inconsistent protrusion/bends can make passing those criteria harder—raising rework probability.

Related Posts

20 Years of Expertise, Trusted by Clients Worldwide

The Preferred Choice of Foxconn, BYD, and Huawei